By 2022, the service plans to field new advanced reactive armor tiles to neutralize incoming warheads, a laser early warning system to warn crews they're being targeted, and a signature management effort to avoid detection in the first place.

Iron Curtain test installation on a US Army Stryker

The Army announced this morning that it has rejected Artis LLC’s Iron Curtain active protection system but will test alternatives in November on its 8×8 Stryker armored vehicle. The Army also will launch three new programs to develop additional types of protection for its armored vehicles, all of which should be fielded by 2022:

New advanced reactive armor tiles that layer on top of a vehicle’s hull armor and explode outward when hit to neutralize impacting warheads.

A laser early warning system to warn a vehicle crew when they’ve been marked by a laser rangefinder or laser beam guidance used by anti-tank weapons.

A signature management effort to reduce the heat, noise, electromagnetic energy, and radar signature that armored vehicles create so they’ll be harder to detect and target in the first place.

Of the three, signature management “is the most mature,” said Col. Glenn Dean, who oversees Army vehicle self-defense systems. “Frankly, we could be deploying that next year if we were funded, (but) right now that isn’t in the 2019 budget.”

Marines train with the Javelin anti-tank missile. Active Protection Systems are designed to shoot down such threats.

Laser early warning is the most technically challenging, Dean told reporters this morning: While sensors that detect incoming lasers aren’t that hard, it requires some sophisticated software to get that warning to the crew in a way they can actually use to protect themselves. Even so, he said, it might be possible to accelerate laser early warning if testing later this year goes well.

As for reactive armor tiles, various types have been in service for decades, but the Army wants to field a new, improved tile and install it as the standard across its entire armored vehicle fleet, Dean said. The new Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), essentially a turretless utility variant of the M2 Bradley, will likely be the first to get the new tiles.

All three efforts fall under the newly named Project Manager for Vehicle Protection Systems, led by Lt. Col. Daniel Ramos. Col. Dean said the service will consider both buying existing systems off the shelf and developing new ones for these functions.

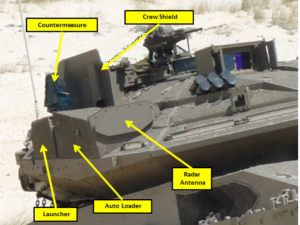

Army M1 Abrams tank with a trial installation of the Israeli-made Trophy Active Protection System (APS)

Active Protection Problems

By contrast, the Expedited Active Protection System (ExAPS) effort is looking only at off-the-shelf technology (Non-Developmental Items or NDI) that can be fielded as fast as possible to confront the Russian threat. That’s why it rejected Iron Curtain.

Iron Curtain “generally was able to hit its targets,” Col. Dean told reporters, but its lacked the “maturity” to function reliably under tough field conditions — in rain, in snow, on vehicles jolting over rough terrain — and it didn’t fit well on the 8×8 Stryker armored vehicle.

Civilian personnel deliver the latest Bradley model, the M2A3, to Fort Riley, KS

The Army is already buying Israel’s Trophy Active Protection System, the only combat proven APS in the western world, for four brigades of its M1 Abramsheavy tanks. (Final “qualification testing” is still underway in parallel). The But smaller vehicles have less room and electrical power to take on new technology.

So the service is still testing the Iron Fist system, also Israeli, on the mid-sized M2 Bradley troop carrier. That work is “about eighth months behind,” Glenn said, for multiple reasons. First, funding for Bradley came through later than for Abrams. Then the contractors needed a lot of time to get Iron Fist working on the Bradley, whose electrical system is notoriously overloaded by decades of upgrades already.. Finally, this summer, stormy weather repeatedly shut down the firing range in Alabama. It’s “about 50 percent through live fire tests right now,” Dean said.

The Iron Curtain, the only US contender, finished testing on the lightweight Stryker in April. Last week, the senior leaders who make up the Army Requirements Oversight Council officially told Dean they had rejected it.

Rheinmetall Active Defense System destroys an incoming threat at the last instant, by design

Fortuitously, Congress had already funded the Army to look at alternative Active Protection Systems beyond the three it started testing last year. In particular, Germany’s Rheinmetal had lobbied hard for its Active Defense System (ADS), which the Army admitted was narrowly edged out when they picked the three initial candidates to test. So the service had already started looking for a fourth candidate system, and it’s currently finalizing formal invitations to interested companies to demonstrate their systems in November. That will almost certainly include Rheinmetal’s ADS as well as a slimmed-down version of Trophy for lighter vehicles.

Even more fortuitously, the Army had already decided to test possible APS on the Stryker. That wasn’t because they were already betting the Iron Curtain would fail, at least as Col. Dean tells the story. Instead, he said, they already happened to have a supply of surplus Stryker hulls, specifically ones left over from the Double V-Hull (DVH) program to improve Stryker underbody protection against roadside bombs and land mines.

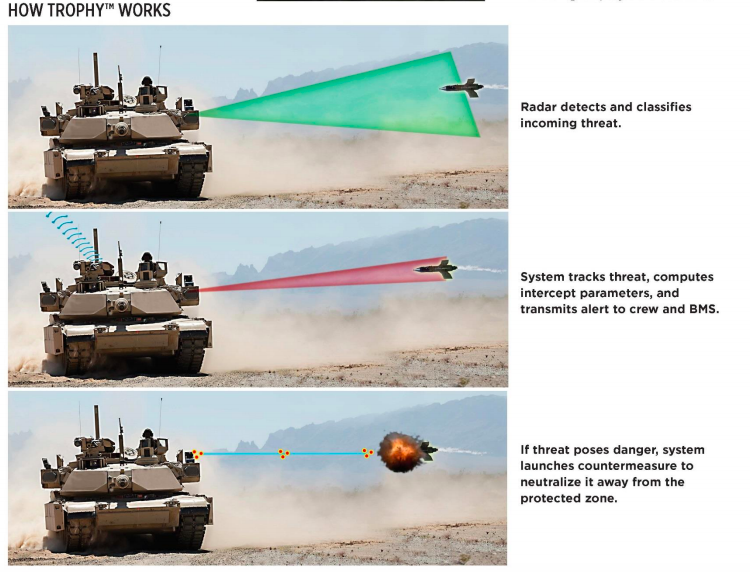

How the Trophy Active Protection System works (Rafael graphic)

Historic Change

Explosive blasts against the underbody and sides of the vehicle were the big threat during the Iraq and Afghan wars, and they’re still a concern given the Russian fondness for land mines. But as the Army refocuses from counterinsurgency to great power war, it has to pay much more attention to rocket propelled grenades and anti-tank guided missiles. Russia has long since fielded its own Active Protection Systems, such as Drozd and Arena, to shoot down incoming RPGs and ATGMs. But western nations have been reluctant, except for Israel, which suffered heavy losses to Hezbollah in Lebanon in 2006 and fielded Trophy in 2009.

Trophy Active Protection System components on an Israeli Merkava main battle tank.

The US Army meanwhile focused on developing its own active protection systems, first IAPS for the Bradley in the late 1990s and then Quick Kill for the Future Combat System in the early 2000s. But FCS was cancelled, and none of the technology could meet the Army’s unrealistically rigorous requirements.

But the US began lowering its expectations as the threat became more urgent, while the Trophy get getting better as the Israelis upgraded it. Finally they met in the middle.

Now, Trophy and most other active protection systems under consideration share a significant limitation. They can shoot down incoming high-explosivewarheads, found on a wide variety of missiles fired by infantry, vehicles, and aircraft, but they can’t stop high-velocity solid shot, essentially armor-piecing metal darts, which only tank guns generate enough kinetic energy to fire. Under congressional direction, this November the Army will test some APS against “tank-fired long rod kinetic energy penetrators as well,” Glenn said, but “I’ll be surprised if we find anything that’s ready.”

Russia’s new T-14 Armata tank on parade in Moscow.

In the long run, however, the Army does want some way to defeat those solid penetrators as well, besides the current solution of piling on ever thicker armor. The new Program Manager – Vehicle Protection Systems will lead the majority of those efforts, Dean said, though highly specialized jamming technology will still fall under PM – Electronic Warfare. PM-VPS will work not only on current vehicles — like Stryker, Bradley, and Abrams — but on future ones, such as the Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF) light tank and the Next-Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV).

What about the Modular Active Protection System, intended as the Army’s long-term solution? MAPS is currently separate, a science and technology effort rather than a development program, Dean said, but it will move into the new PM-VPS at the end of 2019. Between now and then, MAPS will conduct tests of both “hard kill” — i.e. shooting down incoming warheads — and “soft kill” — jamming their guidance systems or decoying them away.

Gen. John Murray, first chief of Army Futures Command, speaks at its formal activation today in Austin.

For its part, PM-VPS will work to make the short-term solutions it’s studying compatible with MAPS. As the word “modular” in its name implies, MAPS is not a specific technology but rather an open architecture with a common set of standards that can accept new upgrades as they’ve developed. Systems that the Army rejects as unready today can come back and try again as they improve, Dean said.

The new Project Manager office is also “kind of unique” organizationally, Dean said. It draws its personnel from two places: Some are from the Program Executive Office for Ground Combat Systems (PEO-GCS), an acquisition organization, but most will come from Research, Development, & Engineering Command (RDECOM).

This hybrid organization embodies the Army’s new approach to developing weapons, which tries to bypass bureaucracy — and rein in unrealistic expectations — by forcing scientists, acquisitions officials, and requirements developers to work closely together. It’s an approach embodied in the service’s high priority Cross Functional Teams working specific priorities. Just today, in Austin, the Army formally stood up the overarching Army Futures Command that will take over the coordinating CFTs, the researchers of RDECOM, and the military futurists of Army Capabilities Integration Command (ARCIC), although acquisition organizations like PEO GCS will remain independent by law. Having squandered two decades on failed modernization programs while Russia and China invested in new weapons, the Army’s future is at stake.

breakingdefense.com