“The fighting, the direction, even the planning of the battles occupies in the whole seconds only to the hours of labor involved in the preparation & execution of marches.”

– Montgomery C. Meigs, US Army Quartermaster General, 1861–1882

Before taking command of an airborne infantry battalion’s forward support company, the company’s second-in-command revealed its soldiers had not qualified on their weapons systems in over a year. In a matter of days, our brigade would become the nation’s Global Response Force and my supported battalion would be the brigade’s first unit to respond to unknown crises across the globe. I was aware of the battalion’s maintenance backlogs, the newly fielded (but untouched) capabilities sets and mission command systems, and the company’s previous struggles to perform the simplest sustainment tasks; but over-simplified criticisms of previous leaders and management did not suffice to explain the full scope of the problems. These problems stemmed from four common dilemmas that young logisticians supporting tactical formations must confront daily.

In a message to cadets preparing to commission as officers across all of the Army’s career fields, Lt. Col. Charles Faint challenged cadets to “own” their respective branches. In the coming months over 660 United States Military Academy and Reserve Officer Training Corps cadets accessed into the quartermaster, ordnance, and transportation corps will report to their respective units. For these future logisticians, their ability to do four things might determine the Army’s success on future battlefields: find balance between training and support, advise their maneuver counterparts on logistical matters, think creatively about the existing capabilities in their formations, and effectively integrate complex technology.

The Gardens of Stone Dilemma

This dilemma speaks to the logistician’s apparent need to train for wartime self-sufficiency while simultaneously supporting others’ preparation for war. Characterized by an imbalance in training and support, the dilemma’s namesake is derived from Francis Ford Coppola’s 1987 film, Gardens of Stone. The film depicts combat-experienced, senior noncommissioned officers struggling to prepare members of the 3rd US Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard) for the crucible of the Vietnam War while simultaneously performing military honors and burials at Arlington National Cemetery.

Army logisticians face a very similar problem. They regularly lack the trainingfor their combat roles. The maneuver unit’s missions and incessant pace of testing, fielding, and integrating new technology and capabilities impose a prodigious commitment in time and training. The logistician acknowledges and appreciates the combat unit’s extraordinary enterprise and expends enormous energy to ensure the maneuver unit’s readiness—normally at the expense of the sustainment unit’s own readiness.

Sustainment units’ wartime unpreparedness is nothing new. Logisticians were ill-prepared for the Korean War, the invasion of Grenada, and the intervention in Somalia. Only days before his unit supported the 1983 Grenada invasion, one support commander noted his unit was “rusty in the field” and lacked “the tactical training required to defend their positions.” In Somalia in 1992–1993, sustainment units “were not prepared or adequately trained to apply the ROE [rules of engagement]” during convoy operations. And only after the highly publicized ambush of the 507th Maintenance Company in 2003 (in which eleven logisticians were killed in action in a convoy outside Nasiriya, Iraq) did the Army take measures to address the tactical shortfalls of sustainment units.

The Orange is the New Black Dilemma

This dilemma could be restated as the “if we’re amber on supplies, then we’re black” dilemma. “Amber” in military vernacular, is the orange-ish hue, part of the green-amber-red-black scale used as a metric for readiness, and is the unreasonably lowest level of logistical risk many commanders are willing to assume. Essentially, if supply limitations push a unit to an amber status on ammunition, fuel, rations, etc., many supported units will treat that as a need for immediate resupply.

The slapdash concern for logistical statuses threaten the Army’s future success, and future logisticians must hurdle this malpractice—occasionally at the risk of their careers. For decades units have relied on installation support at home station and the steadfast availability of supplies on forward operating bases (in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan) to sustain the fight. The absence of highly effective, enemy interdiction operations meant units could operate relatively unhindered by logistical matters. The Vietnam War was well supplied; and ground combat portions of conflicts in Grenada and Panama in the 1980s and Iraq in 1991 lasted no more than a few days—hardly enough time to audition the Army’s advanced logistical apparatus (against much lesser foes, at that).

Accordingly, ground commanders detest (or fear) “amber” logistical statuses and call on sustainment units to respond, often without question, to their every need without much advising from logisticians. These excessive assignments put young logisticians in dilemmatic situations with maneuver commanders (who are sometimes their raters or senior raters) where they are forced to grapple with the question of whether they support by responding to every need, or should propose that resupply can wait based on the information provided by the supported unit.

The “War Rig” Dilemma

The “War Rig” dilemma transpires in the overlapping realms of war and money when logisticians entertain the need for updated equipment while simultaneously acknowledging that such innovation would negatively influence the warfighter’s capabilities. In the opening crucibles of conflict, logisticians quickly adapt their outdated capabilities to wartime realities in manners similar to vehicle modifications depicted in the 2015 film Mad Max: Fury Road.

The film’s most notable machine, aptly named “the War Rig,” was a heavily modified eighteen-wheeler with armored hub caps, a cow-catcher, modified turrets, and more. The War Rig’s crew refashioned the vehicle to address whatever need or threat surfaced in the chaotic, post-apocalyptic world of the unknown. Such improvisation has strong echoes in the field-level modifications such as the hedge-cutters in Normandy in World War II and customized armored gun trucks in Vietnam and in Iraq in 2003–2004.

Very little modernization occurs among sustainment formations during periods of peace. As one Small Wars Journal contributor stated:

Steeped in tradition, our US military has had a love-hate relationship with innovation and change. And while military leaders will enthusiastically embrace tactical innovation on the front line . . . during peacetime leadership is hesitant to support tactical or strategic innovation, especially in organizations more distant from the fight.

Ultimately, the logistician settles for what is provided. Young logisticians must recognize that they are taking charge of formations materially fitted for, at best, the last war. Lessons learned from previous conflicts are rarely translated into material improvements among sustainment formations during periods of peace. For example, the need for internal security (i.e., gun trucks) in sustainment units were identified as early as Vietnam and in Somalia. But by the late 1990s the Army issued its up-armored gun truck inventory to military police and cavalry units—the very type of units committed to their principal missions and unable to provide much assistance to sustainment units. Consequently, during the early months of Operation Iraqi Freedom, sustainment units made War Rig–like adaptions to compensate for their vehicles’ lack of protection and security. Under current equipment authorizations and the 2010 Tactical Wheeled Vehicle Strategy, sustainment units are as demilitarized as before but with an enduring expectation to self-secure by their maneuver counterparts.

The Hoverboard Dilemma

Unlike the previous three dilemmas that have endured in modern military history, the hoverboard dilemma is a budding challenge as the Army adopts more and more technology. This dilemma’s namesake is the craze of 2015 in which Americans across the country rushed to purchase hoverboards. Consumers became enamored with the new product, even though it did not offer the same experience that Marty McFly enjoyed in Back to the Future Part II. Many who purchased the product did not fully understand the challenges or dangers it presented. Arguably, the hoverboard’s most popular outcome were videos on social media of consumers attempting to use the product and subsequently falling and injuring themselves. Aside from the most visible safety risk, many hoverboards unexpectedly caught fire. As the craze dissolved, many hoverboards were thrown into closets after the novelty wore away and never used again.

Similar to the hoverboard craze, when the Army fields new technology and other capabilities, it is unlikely logisticians have adequate time dedicated to fully train and understand its applications. Nor does the Army authorize additional personnel to meet new logistical demands because an increase in sustainment personnel would entail a decrease in maneuver personnel. These facts inhibit successful integration of new capabilities and building the competencies necessary to maintain the equipment without considerable support from field service representatives. In addition, gaps in communications and other capabilities widen between the supported and supporting unit.

I observed this conundrum as a company commander while attempting to integrate capability sets, WIN-T system updates, and new mobility platformsinto my formation. Despite new equipment training and numerous exercises, my company could hardly keep pace with our maneuver counterparts’ proficiency on the systems or the maintenance demands. Similar to the Gardens of Stone dilemma, I erred in favor of the maneuver element at a considerable cost to my own unit’s combat readiness. And as the Army’s technological advantages over near-peer threats decrease, logisticians will be put under additional stress to preserve and maintain our advantages.

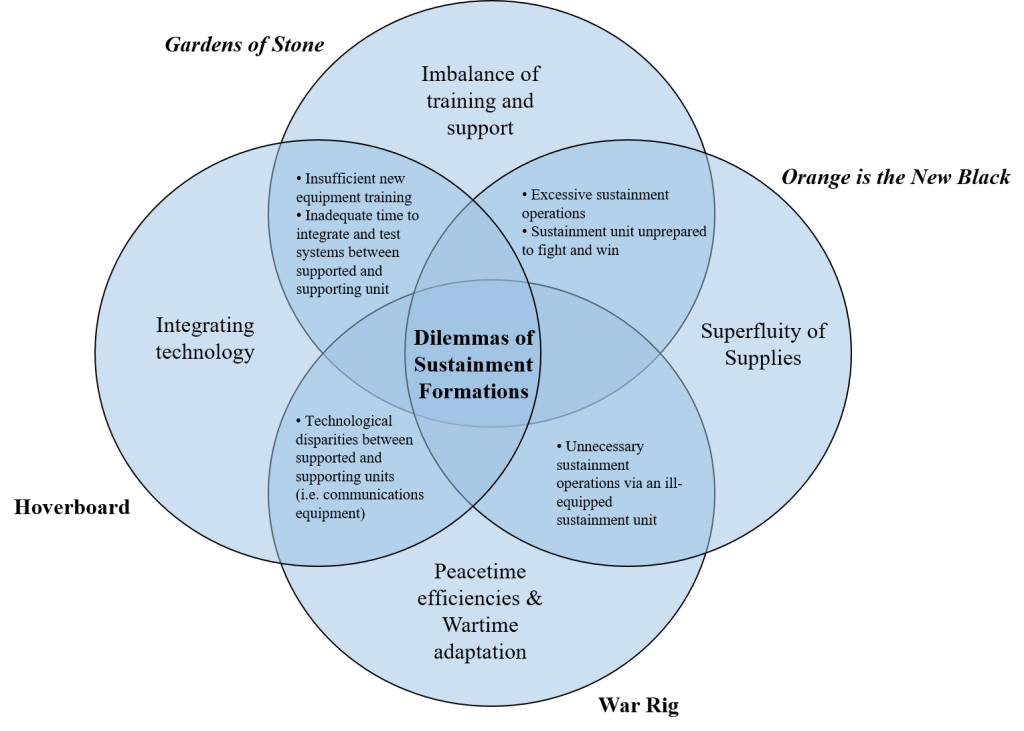

The Four Dilemmas of Sustainment Formations

The Logistician’s Dilemmatic Responsibility

If you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day. If you take a fish from him, you leave him hungry for a day. But if you seize and retain the water source he and his comrades will starve, dehydrate, and lose the will to fight. In the most extreme circumstances, the army dies. Supply-line interdiction remains a tried-and-true means of depriving an army of its capacity to impose its will. Successful interdiction operations have ruined national economies, robbed armies of their sustenance and morale, and left a string of lessons learned for the professional soldier. Depicting these historic failures to protect logistical capacity on a map would resemble a remarkably complex, unfinished “connect-the-dots” puzzle: The Gedrosian desert (325 BCE). Guandu (200 BCE). Carrhae (53 BCE). The Horns of Hattin (1187). Tumu (1449). The Russian Campaign (1812). Holly Springs-Vicksburg (1862). Kalubara (1914). Singapore (1942). Wanat (2008). And many more. The ambitions and life of the armies and soldiers associated with these logistical shortfalls, in many respects, ended with emaciated warriors and nags, frostbitten appendages, dearths of weaponry, empty fuel tanks, a worn spirit—or a wicked combination of all these and more. And so long as the spear of Mars trembles, the record and body count resulting from poorly planned and executed logistics will grow.

Under peacetime fiscal constraints, the Army prioritizes its “teeth” over its “tail”; but as history illustrates military leaders must approach their sustainment units’ combat readiness with creativity and understanding during periods of peace and fiscal constraint. Consequently, tactical sustainment units cannot be trained for their wartime duties without some degree of (undesirable) sacrifice to combat units. “Support to the line” entails a great deal of risk to personnel and supplies, but few maneuver commanders would willingly sacrifice their units’ tactical competency and military expertise over “questions of supply.” Even fewer maneuver commanders would pull warfighters from the line to secure supplies if the supporting unit could manage itself. For these reasons, young logisticians should consider the following practices:

Responsibly mitigate risk now for tomorrow’s war. When possible, design training that compels sustainment units to adapt and share lessons with other sustainment formations. Recognize that sustainment units are not equipped to fight the next war. Review range-control policies and coordinate with appropriate agencies to permit safe training with “adaptations” and unorthodox platforms. Sustainment units may appear ludicrous and primitive under this method, but they are training how they will truly fight.

Make “administrative” and “notional” sustainment a malpractice of the past. Logisticians are in prime positions to enact change and employ sound doctrine in logistical matters. Carefully leverage logistical expertise, make the proper coordination to do what is right, and be responsible for the sustainment unit’s combat readiness—even if it causes minor frustration with the supported unit.

Focus on small units and tactics. Sustainment leaders and literature place an unreasonable emphasis on sustainment perspectives from the operational and strategic levels of war. However, Brig. Gen. Jesse R. Cross, the fiftieth US Army quartermaster general, always boasted that he was a respectable captain before he was a general officer. Likewise, young logisticians must focus their energy to successfully prepare their crews and squads for war before attempting to grasp the complexities of well-designed, highly complex supply chains.

Prioritize support. Priorities of support outlined in operations orders are rarely followed or practiced. If units are reporting an “amber” status and requesting an immediate resupply, learn to say “wait-out” instead of “roger.” This is an exercise of disciplined disobedience. A fully staffed distribution platoon supporting a light infantry battalion has no more than sixteen authorized personnel to support over a dozen platoons in four companies. Responding immediately to every call is unsustainable.

This depiction of Army sustainment should not be interpreted as an indictment of the Army, our government, or the logistician’s combat arms counterparts. It is a testament to the stamina, commitment, and professionalism of the Army’s logistics corps’s promise to sustain victory on any battlefield. For over 660 young logisticians entering the Army profession in 2019, their success will be measured by how well they negotiate the four dilemmas daily, in peace and war. They will find their greatest challenges will occur where these dilemmas intersect; and no single, universal solution may be applied when factors such as unit mission and culture can influence the success or failure of their attempts to negotiate these dilemmas. Supported units, too, might benefit from thinking about sustainment from this perspective. But it is the professional logistician’s responsibility to understand how these dilemmas might inhibit sustainment efforts and propose effective and efficient methods to confront them.