Time-honored principles of command get weird when you add the fundamentally alien thinking of an artificial intelligence.

Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) relies on the JARVIS artificial intelligence to help pilot his Iron Man suit -a model the military is looking at for future troops (Marvel Comics/Paramount Pictures)

ARMY WAR COLLEGE: What happens when Artificial Intelligence produces a war strategy too complex for human brains to understand? Do you trust the computer to guide your moves, like a traveler blindly following GPS? Or do you reject the plan and, with it, the potential for a strategy so smart it’s literally superhuman?

At this 117-year-old institution dedicated to educating future generals, officers and civilian wrestled this week with how AI could change the nature of command. (The Army invited me and paid for my travel.).

Aegis ships firing missiles

“I’m not talking about killer robots,” said Prof. Andrew Hill, the War College’s first-ever chair of strategic leadership and one of the conference’s lead organizers, at the opening session. The Pentagon wants AI to assist human combatants, not replace them. The issue is what happens once humans start taking military advice — or even orders — from machines.

The reality is this happens already, to some extent. Every time someone looks at a radar or sonar display, for example, they’ve counting on complicated software to correctly interpret a host of signals no human can see. The Aegis air and missile defense system on dozens of Navy warships recommends which targets to shoot down with which weapons, and if the human operators are overwhelmed, they can put Aegis on automatic and let it fire the interceptors itself. This mode is meant to stop massive salvos of incoming missiles but it could also shoot down manned aircraft.

Now, Aegis isn’t artificial intelligence. It rigidly executes pre-written algorithms, without machine learning’s ability to improve itself. But it is a long-standing example of the kind of complex automation that is going to become more common as technology improves.

The inset image shows what the soldier can see through the wirelessly linked ENVG-III goggle and FWS-I gunsight.

While the US military won’t let a computer pull the trigger, it is developing target-recognition AI to go on everything from recon drones to tank gunsights to infantry goggles. The armed services are exploring predictive maintenancealgorithms that warn mechanics to fix failing components before mere human senses can detect that something’s wrong, cognitive electronic warfare systems that figure out the best way to jam enemy radar, airspace management systems that converge strike fighters, helicopters, and artillery shells on the same target without fratricidal collisions. Future “decision aids” might automate staff work, turning a commander’s general plan of attack into detailed timetables of which combat units and supply convoys have to move where, when. And since these systems, unlike Aegis, do use machine learning, they can learn from experience — which means they continually rewrite their own programming in ways no human mind can follow.

Sure, a well-programmed AI can print a mathematical proof that shows, with impeccable logic, how its proposed solution is the best, assuming the information you gave it is correct, one expert told the War College conference. But no human being, not even the AI’s own programmers, possess the math skills, mental focus, or sheer stamina to double-check hundreds of pages of complex equations. “The proof that there’s nothing better is a huge search tree that’s so big that no human can look through it,” the expert said.

Developing explainable AI — artificial intelligence that lays out its reasoning in terms human users can understand — is a high-priority DARPA project. The Intelligence Community has already had some success in developing analytical software that human analysts can comprehend. But that does rule out a lot of cutting-edge machine learning techniques.

Amazon warehouse

Weirder Than Squid

Here’s the rub: The whole point of AI is to think of things we humans can’t. Asking AI to restrict its reasoning to what we can understand is a bit like asking Einstein to prove the theory of relativity using only addition, subtraction and a box of crayons. Even if the AI isn’t necessarily smarter than us — by whatever measurement of “smart” we use — it’s definitely different from us, whether it thinks with magnetic charges on silicon chips or some quantum effect and we think with neurochemical flows between nerve cells. The brains of (for example) humans, squid, and spiders are all more similar to each other than either is to an AI.

Alien minds produce alien solutions. Amazon, for example, organizes its warehouses according to the principle of “random stow.” While humans would put paper towels on one aisle, ketchup on another, and laptop computers on a third, Amazon’s algorithms instruct the human workers to put incoming deliveries on whatever empty shelf space is nearby: here, towels next to ketchup next to laptops; there, more ketchup, two copies of 50 Shades of Grey, and children’s toys. As each customer’s order comes in, the computer calculates the most efficient route through the warehouse to pick up that specific combination of items. No human mind could keep track of the different items scattered randomly about the shelves, but the computer can, and it tells the humans where to go. Counterintuitive as it is, random stow actually saves Amazon time and money compared to a warehousing scheme a human could understand.

Champion poker players lose hand after hand to the Libratus AI

In fact, AI frequently comes up with effective strategies that no human would conceive of and, in many cases, that no human could execute. Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov at chess with moves so unexpected he initially accused it of cheating by getting advice from another grandmaster. (No cheating — it was all the algorithm). AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol with a move that surprised not only him but every Go master watching. Libratus beat poker champions not only by out-bluffing them, but by using strategies long decried by poker pros — such as betting wildly varying amounts from game to game or “limping” along with bare-minimum bets — that humans later tried to imitate but often couldn’t pull off.

If you reject an AI’s plans because you can’t understand them, you’re ruling out a host of potential strategies that, while deeply weird, might work. That means you’re likely to be outmaneuvered by an opponent who does trust his AI and its “crazy enough to work” ideas.

As one participant put it: At what point do you give up on trying to understand the alien mind of the AI and just “hit the I-believe button”?

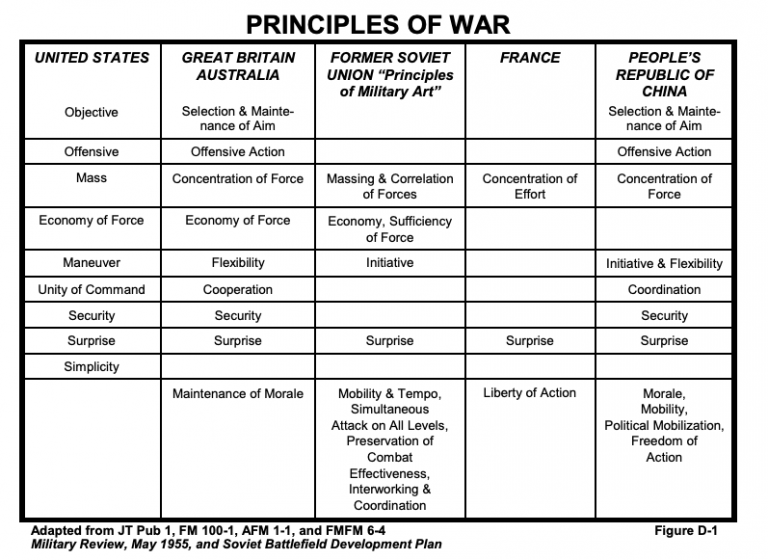

SOURCE: Joint Staff Officer’s Guide

The New Principles of War

If you do let the AI take the lead, several conference participants argued, you need to redefine or even abandon some of the traditional “principles of war” taught in military academies. Now, those principles are really rules of thumb, not a strict checklist for military planners or mathematically provable truths, and different countries use different lists. But they do boil down centuries of experience: mass your forces at the decisive point, surprise the enemy when possible, aim for a single and clearly defined objective, keep plans simple to survive miscommunication and the chaos of battle, have a single commander for all forces in the operation, and so on.

A soldier holds a PD-100 mini-drone during the PACMAN-I experiment in Hawaii.

To start with, the principle of simplicity starts to fade if you’re letting your AI make plans too complex for you to comprehend. As long as there are human soldiers on the battlefield, the specific orders the AI gives them have to be simple enough to understand — go here, dig in, shoot that — even if the overall plan is not. But robotic soldiers, including aerial drones and unmanned warships, can remember and execute complex orders without error, so the more machines that fight, the more simplicity becomes obsolete.

The principle of the objective mutates too, for much the same reason. Getting a group of humans to work together requires a single, clear vision of victory they all can understand. Algorithms, however, optimize complex utility functions. For example, how many enemies can we kill while minimizing friendly casualties andcivilian casualties and collateral damage to infrastructure? If you trust the AI enough, then the human role becomes to input the criteria — how many American soldiers’ deaths, exactly, would you accept to save 100 civilian lives? — and then follow the computer’s plan to get the optimal outcome.

Finally, and perhaps most painfully for military professionals, what becomes of the hallowed principle of unity of command? Even if a single human being has the final authority to approve or disapprove the plans the AI proposes, is that officer really in command if he isn’t capable of understanding those plans? Is the AI in charge? Or the people who set the variables in its utility function? Or the people who programmed it in the first place?

The conference here didn’t come up with anything like a final answer. But we’d better at least start asking the right questions before we turn the AIs on.