The US Army wants a lot out of its Black Hawk replacement, at $43 million apiece -- but the Marines and special operators want even more.

Bell V-280 Valor tiltrotor in level flight with rotors facing forward. The V-280 is widely considered the leading candidate for the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA)

Bell V-280 Valor tiltrotor in level flight with rotors facing forward. The V-280 is widely considered the leading candidate for the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA)

To ensure its Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft can survive a war with Russia or China, the Army wants radically superior speed and range compared to current helicopters. But a joint Request For Information released yesterday shows that the tech-savvy Special Operations Command and the hard-charging Marine Corps want even more.

Bell’s proposed V-280 Valor attack variants

The Marines in particular want not only extreme range and speed — because they have to fly from ship to shore and then inland — but additional features like in-flight refueling capability and built-in weapons. The Marines also want a gunship (attack) variant of the aircraft as well as the baseline transport (assault).

On the other hand, while the Army has the least ambitious performance specs (which are still pretty ambitious), it’s the only service so far to set a price target: no more than $43 million per aircraft. The Marine and SOCOM versions will certainly cost more.

These differences are especially significant because the people who want the most out of the aircraft are also the least committed to buying it if it underperforms. While the Army’s pretty much committed to buying FLRAA to replace its thousands of UH-60 Black Hawks, SOCOM and the Marines may take some convincing to join the buy. Yes, the Army’s by far the biggest customer, but industry definitely doesn’t want to lose out on the other two.

Army National Guard troops practice offloading their AH-64 Apache gunship from an Air Force C-17 jet transport.

Now, none of this is final. The Request For Information is just that, a document asking industry for information — specifically, whether it’s actually feasible to build something with this performance on budget and on schedule. Industry can always say “uh, no” and there’s a good chance the military will listen. The Army, for example, recently reined in protection requirements for its Next Generation Combat Vehicle to replace the M2 Bradley, because industry looked at the draft requirements and said the machine would just be too heavy and bulky to fit two of them in a C-17 transport plane.

All these programs are part of a much bigger push to overhaul the Army for future war against great powers. New armored vehicles are No. 2 of the Army’s Big Six modernization priorities, with new aircraft (aka Future Vertical Lift) at No. 3; ultra-long-range artillery is Priority No. 1. The Army’s seeking quantum improvements across the board to its current technology, most of it initially fielded 40 years ago during the Reagan buildup. For aircraft, that means conventional helicopter designs won’t cut it, driving the leading contenders to offer hybrids of helicopter and propeller driven plane: Bell’s V-280 Valor tiltrotor (above) and the Sikorsky-Boeing team’s SB>1 Defiant compound helicopter (below).

The Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 Defiant on its first flight, March 21, 2019.

By the Numbers

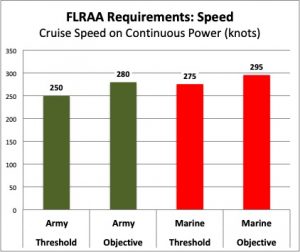

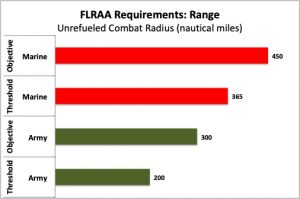

So what, specifically, do the different services want? Some key numbers:

FLRAA: Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft

Speed: The Army’s minimum acceptable cruise speed, the threshold requirement, is 250 knots (288 mph); its preference, the objective requirement, is 280 (322 mph, incidentally the intended cruise speed of Bell’s V-280). The Marines’ threshold is 275 knots (316 mph), almost as high as the Army’s objective; their objective is 295 (339). And that actually understates the difference, because the Army only asks for this performance at maximum continuous power — the highest the engine can sustain over a long flight — while the Marines want it at 90 percent of maximum continuous power.

The Marines have even higher speed requirements for brief sprints, something the Army doesn’t address. Special Operations doesn’t set specific speed requirements, which means they’re okay with the Army’s.

Range: The Army threshold for unrefueled combat radius — how far the aircraft can fly out and do a mission before it has to come back to base for gas — is 200 nautical miles (230 regular miles); its objective is 300 nm (345 miles). The Marines’ threshold is above the Army objective: They want at least 365 nm (420 miles). They’d prefer 450 (518 miles). Again, SOCOM is okay with the Army requirements here.

The difference is driven by different missions. The Marines are usually flying from their ships, which have to stay increasingly far at sea to avoid anti-ship missiles launched from shore. So in the FLRAA Request For Information, the Army outlines missions for air assault (i.e. landing troops), air assault on mountains specifically (harder because of the high altitude), hauling a howitzer (slung underneath the aircraft on cables), and medical evacuation, with unrefueled ranges required from 88 to 190 nautical miles (101 to 219 miles). The Marines, by contrast, want both the baseline troop-carrier and the upgunned attack variant to go out 365 nautical miles (420 miles).

To further extend the range, the Marines also want their version to have a full kit for in-flight refueling from tanker aircraft. The Army is willing to accept an aircraft with room to add refueling gear. SOCOM is in the middle: They want a refueling system available as a “b-kit” installation for selected aircraft, but not as a standard feature.

Marine Corps V-22 operating from the carrier USS Bush

Deployment: SOCOM has just one other unique requirement, but it’s a big one. They need their variant to fit in an Air Force C-17 cargo jet for transport. That puts a limit on the aircraft’s maximum size and also requires an easy way to fold up rotors, wings, and other protruding pieces.

The Marines, of course, want the aircraft to fit on a Navy amphibious warfare ship — admittedly a lot roomier than a C-17, but hardly spacious — and to keep functioning despite high humidity and saltwater corrosion. They also want a built-in gun on the transport version, and a lot more weapons on their assault variant.

A UH-60 Black Hawk takes off after unloading soldiers during an air assault exercise in Germany.

Passengers: On the other hand, the Marines are willing to make one concession in payload. While the Army (and SOCOM) want room for 12 people beside the pilots, all of them heavily laden combat infantry, the Marines are okay with 10: two additional aircrew (e.g. a crew chief manning the gun), and eight riflemen.

With 365 pounds allotted for each infantryman and their kit, reducing the number of passengers even slightly makes a major difference, for example by making room for more fuel. But it won’t be enough, by itself, to make up for all the performance improvements the Marine Corps wants.

Timeline: The Army wants to award a contract by the fall of 2021, with the first flight in 2024 and the first unit fully equipped and ready to go in 2030, although it also asks industry for proposals to “accelerate the program as much as possible.” The SOCOM and Marine Corps schedule will run “approximately two years later,” the RFI says.