Army foot soldiers are going into battle with more and more electronics, wirelessly networked both to each other and to distant command posts. So can GI Joe be hacked?

The inset image shows what the soldier can see through the wirelessly linked ENVG-III goggle and FWS-I gunsight.

Wifi gunsights that tell your smart goggles where to aim. Artificial intelligence that tells distant artillery batteries whenever you spot a high-priority target. Backpack transmitters, remotely controlled by technicians miles away, that jam enemy communications while you focus on the fight. Ajamming-resistant GPS that double-checks your location against a wearable inertial navigation system and pedometers in your boots. These are all technologies the Army is now developing or, in some cases, fielding in a few months.

The American grunt has gotten ever more high-tech since 2001. Handheld GPS, tactical radios, night vision goggles, electronic gunsights, and more have accumulated to the point where the weight of batteries has become a major burden.

The new FWS-I gunsight (Family of Weapons Sights – Individual) can link wirelessly to advanced night vision and targeting goggles to improve the wearer’s aim.

But now the Army aims connect all these devices in a wearable, ultra-short-range wifi network around the soldier’s body and, in many cases, over long-range battlefield networks as well.

This trend is a distinctly double-edged. On the upside, the kind of near-instantaneous sharing of data — on friendly locations, reported threats, potential targets — is exactly what the Army and its sister services need to coordinate the kind of high-speed, high-complexity multi-domain operations they see a crucial to victory on future battlefields. On the downside, the likely enemies on in such future fights, like Russia and China, are scarily good at jamming, spoofing, hacking, and disrupting wireless networks. That requires a new kind of muddy-boots cybersecurity.

Soldiers train with the IVAS augmented-reality headset at Fort Pickett.

Connect & Secure

The modern soldier is increasingly “an integrated weapons platform,” like a tank or helicopter, said Brig. Gen. Tony Potts, the Army’s acquisition chief for soldier gear (aka PEO-Soldier). “I want everything within a squad to be able to talk to each other.”

To move all that data, “we are building our own processors, we’re going to spin our own chips … because we needed processors more powerful and faster than we had commercially available,” Potts said. “They’re going to be on-body processors… part of a hybrid cloud system” that pulls data from far-off servers.

But when everything is interconnected, you have to take new kinds of precautions, Potts warned the TechNet Augusta conference this week. So, since he took over as Program Executive Officer – Soldier early last year, Potts has pushed hard to get the systems in his portfolio to comply to strict standards for cybersecurity.

“When I got there 18-19 months ago, most of the things that we did [got] waivers for all that cybersecurity stuff: ‘Hey, sir, we don’t need that, they’re just goggles,'” Potts recounted. “Now in [PEO] Soldier, we’re now having to build a very robust capability for RF [radio frequency, i.e. wireless] cybersecurity, because everything we are doing … we are moving and sharing all that data across the soldier as a platform and across the squad as a platform, and we’ve got to protect that data.”

Many of the devices foot troops already carry, in fact, send and receive data over the wider tactical network with other units, from command posts to artillery batteries. That allows unprecedented cooperation, but also unprecedented vulnerability for an enemy to hack one system and then spread malware or bad data around the entire network.

Today, for example, PEO-Soldier produces all the precision-targeting devices that troops used to call in fire support, Potts said. For the near future, Army’s augmented-reality goggles known in development — a militarized Microsoft HoloLens known as the Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS), aka HUD 3.0 — will display both information from the soldier’s personal electronics, such as a targeting cross-hairs showing where his gun is pointed, and tactical information from the battlefield network, like the distance and direction to the objective. IVAS is also exploring an artificially intelligent object-classification system that can automatically recognize, say, an anti-aircraft missile launcher in the soldier’s field of view and transmit its coordinates to the network, warning friendly aircraft to steer clear and prompting friendly artillery to destroy it.

The Transportation Department is working closely with DoD, DHS and other agencies “to address policy and technical issues including the security and resilience of GPS receivers,” says General Counsel Steven Bradbury.

Then there’s the invisible weapons of electronic warfare. The Army acquisition PEO for Intelligence, Electronic Warfare, & Sensors has urgently fielded portable radio-detection and radio-jamming systems, VROD and VMAX, in both Europe and the Middle East. Standard procedure is to issue these rucksack-sized systems to specially trained electronic warfare troops, who use a tablet to control them. Typically three or four EW troops go out together — so they get multiple bearings on a signal and triangulate — with a squad of regular infantry as escorts.

But mere months from now, the Army will issue new electronic warfare command-and-control software, EWPMT, which will allow a single EW technician in a distant command post to control multiple VROD or VMAX systems all over the battlefield.

“It can be put on any soldier’s back and remoted through EWPMT,” PEO-IEWS expert Ken Gilliard told reporters at Aberdeen Proving Ground last week. That means the infantryman carrying it can focus on things like running, shooting, and not getting killed, while the Army’s relatively small number of EW technicians can hunker down behind the frontline and control the digital battle over a wide area.

But that also means enemy electronic warfare technicians can potentially detect the transmissions back and forth, then use them to fix the US troops’ location or, arguably worse, hack into the American battlefield network.

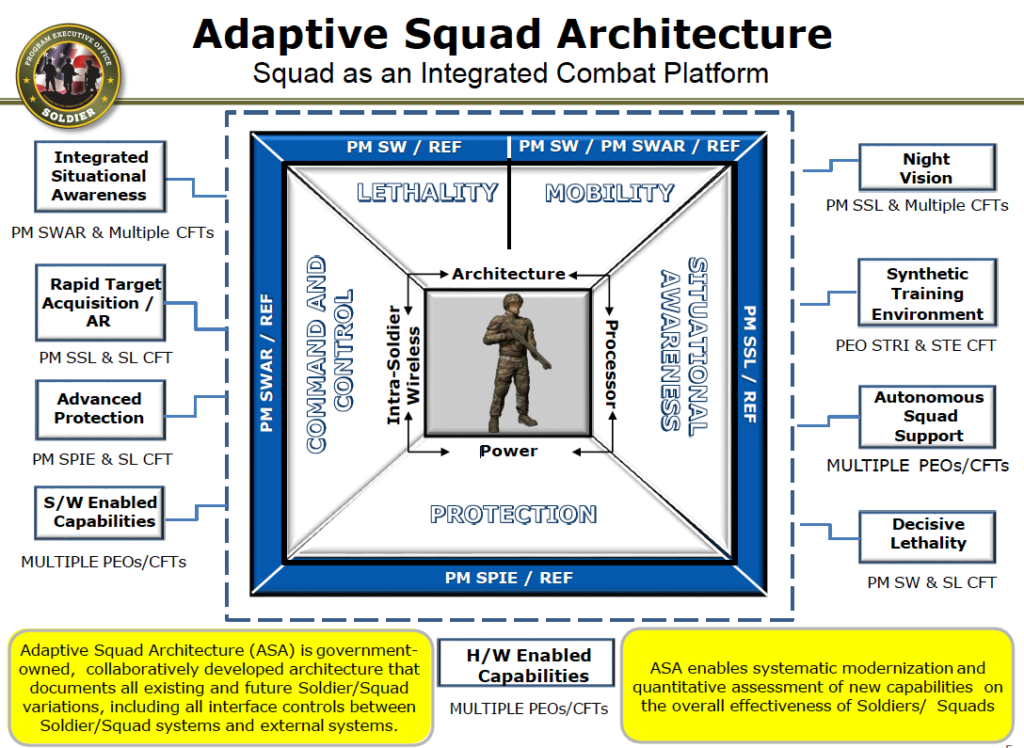

The new IVAS headset will be the linchpin at the center of an Adaptive Squad Architecture to connect soldiers’ electronics.

Standards & Collaboration

PEO-Soldier is working with the network modernization team to ensure all the soldier-borne tech connects reliably and securely with the wide-area battlefield wifi, Potts said. He’s also working with the teams developing new armored vehicles and aircraft so that, when soldiers get in and out of their transports, they remain connected to the network. And he’s joined at the him with the Army’s director for training systems modernization, Maj. Gen. Maria Gervais, so her simulators can run on his IVAS goggles, which will troops train against VR enemies who pop up in their field of vision like a hardcore version of Pokémon Go.

But it’s tricky enough just getting all the different systems the infantry squad carries to connect to each other. To make that simpler, PEO-Soldier is developing what they call the Adaptive Squad Architecture (ASA) that specifies how contractors must configure whatever component they built to interconnect with the others, with IVAS as the central pillar of the entire structure.

Infantry wargames at the Joint Readiness Training Center, Fort Polk, La.

“Adaptive Squad Architecture, we’re building the tools today,” Potts said. “We’re actually. going to release an early version in January.”

“We had an industry day earlier this week,” he went on, where he explained to industry he has no designs on their intellectual property, he just wants them to build tech compatible with the new architecture so everything works together — an approach called open architecture. “I don’t want to own a lot of proprietary things,” Potts said. “I want to own the interfaces, and I want you to know what those interfaces are.”

The ultimate goal is a layered system that degrades gracefully. If jamming, hacking, reinforced-concrete buildings, or an intervening hill you off from the wide-area battlefield network, you can at least share data within your squad. If you’re cut off from your squad, you can at least share data among the devices you wear and carry. And if everything is cut off — well, your IVAS still has night-vision built in. “Worst case is I lose it all and it’s a set of goggles,” Potts said.

The Army needs to build its kit — and train its soldiers — to keep functioning even if every network connection is shut down, but make the most of all that data when and if they get it. “We need to be networked-enabled and not network-dependent,” Potts said. “We have to build our systems where, if I’m completely denied connectivity, I can still fight.”