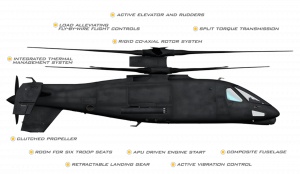

The Sikorsky Raider-X, Lockheed Martin’s proposed design for the Army’s Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft

So how does Raider-X, with its two coaxial, counter-rotating rotors on top and pusher propeller in back, compare to its much more traditionally designed rival, the Bell 360 Invictus, which has a single main rotor and small tail rotor for stability? In a Friday interview Friday with me and Aviation Week’s Graham Warwick, one sign of Sikorsky’s confidence was how eagerly its execs invited that comparison, though they spoke in generic terms about single-main-rotor helicopters rather than bashing Bell by name.

Bell 360 Invictus concept

(Three other contenders received awards to propose FARA designs – Boeing, Karem, and an AVX/L3 Harris team – but we haven’t covered them as extensively. That’s in part because none of them has released nearly as much information. It’s in part because Sikorsky and Bell clearly see each other as the main competition, being the only two companies that won Joint Multi-Role Demonstrator funding to build cutting-edge prototype aircraft).

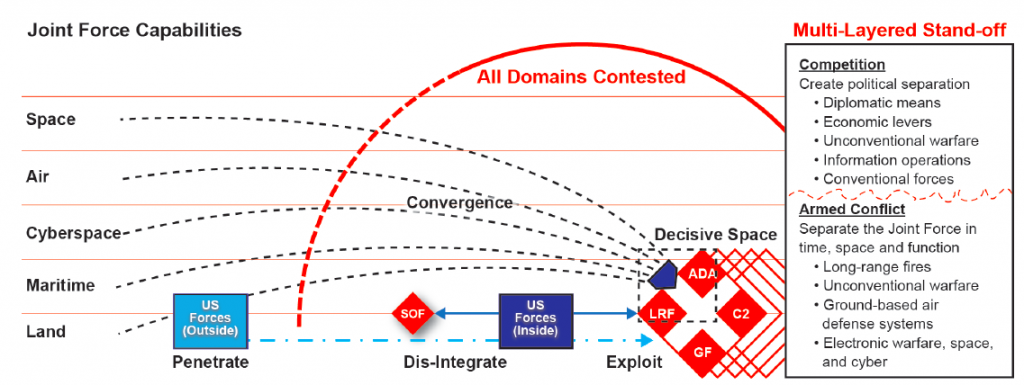

SOURCE: Army Multi-Domain Operations Concept, December 2018.

The Need For Speed On Future Battlefields

To traverse sprawling future multi-domain battlefields and dash past enemy anti-aircraft defenses, the Army wants FARA to go fast. Even at its cruise speed – the fastest speed an aircraft can sustain long-term without damaging the engine – FARA needs to go at least 180 knots (207 mph), 16 percent faster than the AH-64 Apache gunship. The Army also wants FARA to be able to dash in emergencies at 205 knots, though that’s not mandatory.

Sikorsky’s engineering studies showed that, “[with] the 180 knot threshold requirement for FARA, you could get there with a single main rotor, but you were basically topped out,” said Tim Malia, Sikorsky’s director for Future Vertical Light – Light. That’s because conventional helicopters suffer something called retreating blade stall at high speeds, which leads to exponentially increasing drag that takes exponentially more power to overcome, until it becomes physically impossible to accelerate further. (In brief, the diminishing returns diminish all the way to zero). Sikorsky’s engineering studies showed that, to get a single-main-rotor helicopter to reach the speeds the Army wants, you need to squeeze every drop of power from the engine and streamline the airframe ruthlessly to reduce drag.

Indeed, when Bell briefed reporters about their FARA design two weeks ago, they detailed how they’d applied all their engineering expertise to reducing drag: from the needle nose, to the narrow tandem cockpit with one co-pilot sitting in front of the other, to the deliberately off-center tail rotor. Bell also added small wings – a feature not found on conventional helicopters — to provide more lift at higher speeds, allowing the main rotor to spend less energy providing lift and more on thrust. Even so, to get enough thrust, Bell felt compelled to include a “supplemental power unit” to boost the main engine (a GE T901 Improved Turbine Engine).

All that effort is to get the Bell 360 to sustain 180 knots. What about the 205 knots bursts of speed that the Army wants? That’s not a mandatory requirement, Bell exec Keith Flail said over and over again.

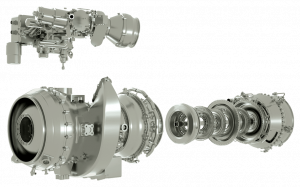

By contrast, Sikorsky is confident their Raider-X can beat 205 knots – using the same GE T901 engine as the Bell 360, but with no supplemental power system. Raider doesn’t need wings, either. The ultra-rigid rotors provide all the lift required at high speeds, relying on the pusher propeller to provide thrust. And, while streamlined, Raider-X’s fuselage is actually fairly wide: The co-pilots are seated side-by-side – making it easier for them to see each others’ displays and point things out to each other – with a cabin behind them large enough for passengers or a capacious weapons bay.

“We weren’t trying to get every last bit of drag out to hit a speed requirement. We didn’t need to,” Malia said. “We are not doing anything cute or tricky by trying to add additional engines. We are using the power that’s available from the T901, and we’ve got a really solid design built around it.”

Sikorsky’s smaller and less powerful S-97, which has the same side-by-side cockpit design, has already done 207 knots in tests, beating the Army’s dash-speed requirement. The grandfather of the Sikorsky compound-helicopter family, the Collier Trophy-winning X2 tech demonstrator, managed 250. Considering this history, and reading between the lines of what Malia and other execs have said, it seems Sikorsky is actually deemphasizing speed with each new generation of compound helicopter so they can focus on optimizing other features.

Sikorsky S-97 Raider on its first flight

Agility, Reliability, Cost, and History

It’s those other features besides speed where Bell says it has the advantage: low-speed agility, mechanical reliability and ease of maintenance, and low cost.

Sikorsky counters they’ve put the S-97 through extensive agility testing, meeting Army standards. They say their expertise in building digital fly-by-wire controls is more than equal to Bell’s. And they say their ultra-rigid rotor blades are more responsive in tight maneuvers than the relatively wobbly rotors that conventional helicopters require.

What’s more, because the rigid rotors don’t need to flex as much as traditional ones, the rotor hub on which they’re mounted requires far fewer moving parts – all told, half as many on the Raider-X as on the UH-60 Black Hawk — which should reduce breakdowns and maintenance.

What about Raider-X’s pusher propeller, a complex piece of machinery that compound helicopters have, but conventional ones don’t? Well, that replaces the traditional tail rotor and its drive shaft, which are also mechanically complex. The difference, Sikorsky says, is that a single-main-rotor helicopter whose tail rotor breaks down – or is destroyed in combat – needs to make an emergency landing immediately or crash. A compound helicopter whose pusher propeller breaks or is destroyed won’t be able to reach its top speeds, but it’s still capable of flying home.

All that said, Bell does have a point. Single-main-rotor helicopters like their Bell 360 have been flying by the tens of thousands since the first workable helicopter – designed and piloted, ironically in this context, by Igor Sikorsky – first took off in 1939. Dual-main-rotor designs like the Boeing CH-47 Chinook – which first saw service in Vietnam — have, likewise, been flying in large numbers for decades.

By contrast, compound helicopters, which combine dual main rotors with new ultra-rigid blades and a pusher propeller, are a much newer technology – and Sikorsky has only built four of them.

The pioneering X2, first flown in 2008 and now retired to the Smithsonian;

A pair of S-97 Raiders, one of which was totaled after a software glitch caused its two sets of rotors – which are set very close together to reduce drag – to clip each other during taxiing; and

The SB>1 Defiant, a transport variant and potential competitor for the Army’s Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft, which is three times the Raider’s size and whose first flight was delayed for months by, among other things, problems building ultra-rigid blades that were big enough.

Now, the Raider-X shouldn’t have the same problems of scale: At 14,000 pounds, it’s only 27 percent bigger than the 11,000-pound S-97, whereas the 30,000-lb Defiant is almost three times as large. But it’s still a new technology, and – assuming the Army likes the Raider-X design well enough to pay Sikorsky to build a prototype – it will be only the fifth compound helicopter Sikorsky has ever made.

The Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 Defiant on its first flight, March 21, 2019.

To Sikorsky, the newness of the technology is a selling point. Whereas traditional single-main-rotor technology has reached the limits of its performance, Sikorsky argues, compound helicopters have decades of growth ahead. When GE next upgrades its T901 engine, for example, Raider-X could easily translate more power into more speed and payload, Malia argued, while a single-main-rotor helicopter like the Bell 360 has already reached the point of diminishing returns where increases in power probably won’t translate into greater speed.

For Raider-X, he said, “the technology itself is at the beginning of its growth curve.”

But new technology comes with greater risk of schedule slips and cost overruns. Today’s Army is willing to abruptly disqualify competitors for a modest delay – as it proved on the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle program – and it’s increasingly anxious about cost. One of the requirements for the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft, alongside speed, is an average cost per aircraft equal to the Apache, about $30 million.

Can Sikorsky compete under that cap?

“We have done a complete affordability analysis,” Malia said. “We’re extraordinarily confident we will come in under the Army’s cost goal.”