20th century warfare was like football, with lines, phases, and pauses, the head of Army Futures Command told us. 21st century conflict is like hockey: unrelenting, brutal, and chaotic. So how do you coordinate your players well enough to win?

“If you’re talking about future ground combat, you’re not talking tens of thousands of sensors,” Gen. John “Mike” Murray told me here. “We’ve got that many in Afghanistan, right now. You’re talking hundreds of thousands if not millions of sensors.”

How do you make sense of all that data for human soldiers and commanders?

“That’s why machine learning, artificial intelligence – especially broader artificial intelligence — is so critical,” the chief of Army Futures Command replied.

We are not the only country developing military AI, of course. What if an enemy takes the human out of the loop, letting their algorithms decide whom to kill so they can kill us faster than we can react?

“Do I think it’s insurmountable? No,” he said. “Because I think our ethics and our concern for the value of human life are actually a strength, and not a weakness.”

Amidst a grueling round of congressional hearings last week, Murray sat down with me for an impromptu interview. We began by going into detail on Iron Dome, the Israeli-built anti-rocket system that Congress pressed the Army to buy, but which the service is struggling to make compatible with its own Integrated Air & Missile Defense Battle Command System, aka IBCS. (You can read that story here).

IBCS command post (Northrop Grumman graphic)

The IBCS network, however, was just a stepping-stone to a much broader discussion, because IBCS is just one piece of the only partly-finished puzzle that is command and control in a future war.

To share data rapidly across all four armed services in all five domains of warfare – land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace – Defense Secretary Mark Esper has an elite Pentagon team working out a new concept for what’s being called Joint All-Domain Command & Control. The Army and the Air Force have been working closely together on this problem for the last few years, with the Navy and Marines more on the sidelines.

But now the Army generals are getting nervous about whether the Air Force’s nascent Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS), designed to link hundreds of aircraft together with sensors in space, on ships and on land, can also handle the data needs of many thousands of ground troops and vehicles. They would prefer to plug together contributions from different services, each optimized for a specific purpose but compatible with the others so they can share data.

The biggest piece of that Army contribution would be IBCS, which is already designed to link any radar in the Army – and, in some experiments, Air Force F-35s – with any Army anti-aircraft or missile defense launcher, sharing data through a standard command post to find the best weapon to take down any given target. Connecting “any sensor to any shooter via any command & control node” this way is a model that can be extended beyond missile defense to offensive warfare as well, the Army says.

But it’s not just IBCS. The Army also wants to build on its investments in the new Integrated Tactical Network for ground maneuver forces – which will get regular upgrades, called Capability Sets, every other year – and on its new Command Post Computing Environment. How will the Army make the case that all these systems need to find a place in the new all-service, all-domain JADC2 network?

Well, let’s ask General Murray.

What follows is our transcript of the relevant portions of our interview, edited for brevity and clarity. Since Murray was supposed to give a keynote speech next Wednesday at the coronavirus-cancelled AUSA Global Force conference, we hope this interview gives our readers an alternative way to know what the leader of Army Futures Command is working on.

Q: How does the IBCS network fit into the larger context of a Joint All-Domain Command & Control system?

A: Arguing with JADC2 is like arguing with free parking in Washington, D.C. Who can argue with any sensor, any shooter, any C2 network, in near real-time?

What we’re doing with IBCS is similar to what the Air Force is doing with ABMS in terms of trying to connect specific platforms. But they’re not exactly the same. We believe fundamentally what is different about what we’re doing is we’re trying to build an architecture from the ground up that will plug into the joint architecture.

IBCS is a key piece of that in the air defense realm, but also we have things like Command Post Computing Environment. You have things like the Integrated Tactical Network that Pete Gallagher‘s working on. We have things like the secretary [Ryan McCarthy] is pushing about cloud computing in data architectures, and data standards, and computing at the edge.

The Air Force will say ABMS is the answer to the joint force in terms of JADC2. [But] ABMS is not going to solve all the problems and IBCS isn’t going to solve all the problems. It’s much bigger than that.

As we build this from the bottom up and the Air Force builds this from the top down, what we’re asking the joint staff to do is, ‘give us that architecture you expect us to plug into and we will build out our systems.’

The concern, Sydney, is if we can’t inform that architecture, we’ve got $32 billion invested in the network. What we don’t want to have happen is [the Pentagon tells us], ‘here’s the architecture we’re all going by, start over.’

You have to inform the build out of this architecture with what, not only the Army, but with what the Air Force, the Navy, the Marine Corps already have going on. We [have to] account for all this and plug it into the architecture.

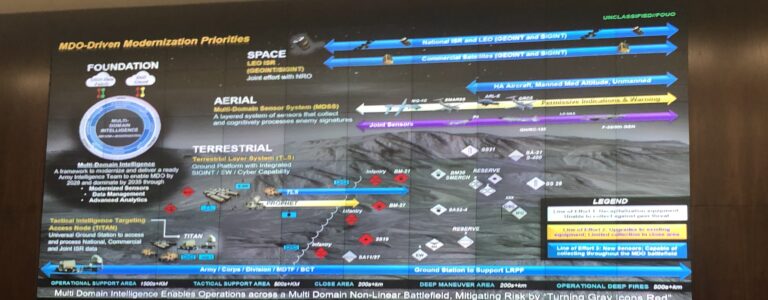

The Army’s proposed Multi-Domain Intelligence system combining space, air, and ground assets.

Q: I keep hearing subtly different formulations of what that new JADC2 architecture is supposed to connect. First it was “any sensor connecting to any shooter through any command & control node.” Then I heard “every sensor, every shooter, every C2 node,” and “best sensor, shooter, C2.” And just today I heard how the enemy may jam your communications, so you won’t have necessarily be able to access every sensor, shooter, C2, or even just the best ones, but you need to connect the best available.

A: I’ll try this out on you. So it started off ‘any,’ I changed it to ‘all.’ And I did that for a reason.

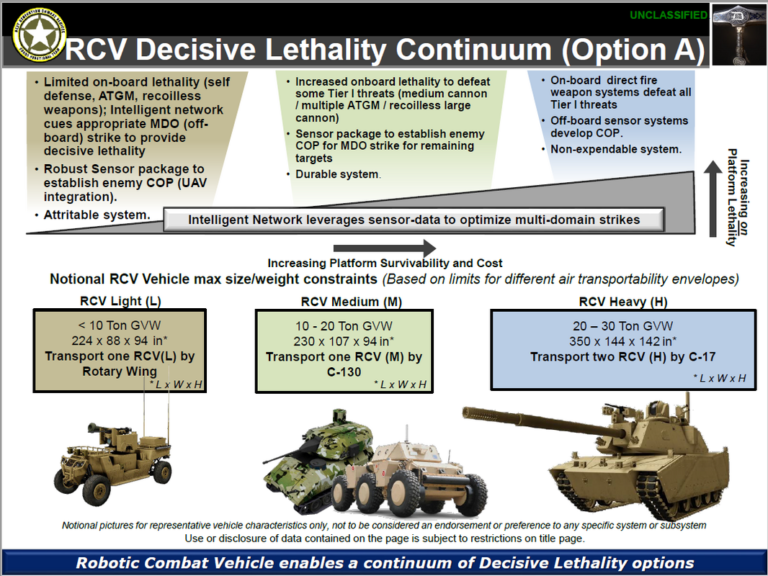

Really, if you’re talking about future ground combat, you’re not talking tens of thousands of sensors. We’ve got that many in Afghanistan, right now. You’re talking hundreds of thousands if not millions of sensors. Where every soldier with an IVAS goggle on is a sensor, every robotic vehicle is a sensor, every munition is a sensor…

Q: And it gets even more complex, since each of those platforms may have multiple different sensors on it – visual, infrared, radar….

A: Exactly.

And that’s why machine learning, artificial intelligence – especially broader artificial intelligence — is so critical: So you can make the ideal pairing between sensors and shooters in near real time.

It’s all about the data and it’s all about the data architectures. That’s so critically important, having this overarching joint architecture so we understand what the architecture looks like. So we can, as we build this out, we can plug into, it’s critical.

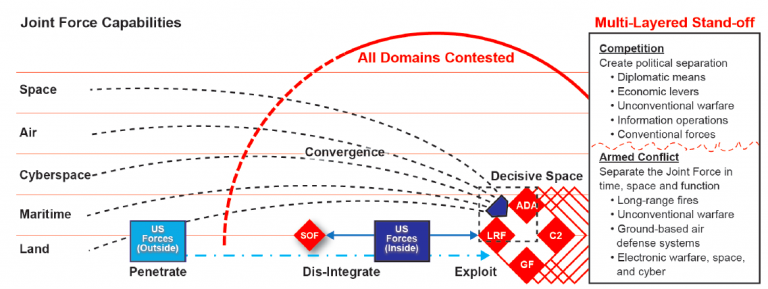

[What that allows] is this concept called convergence. It’s a key tenet of Multi-Domain Operations.

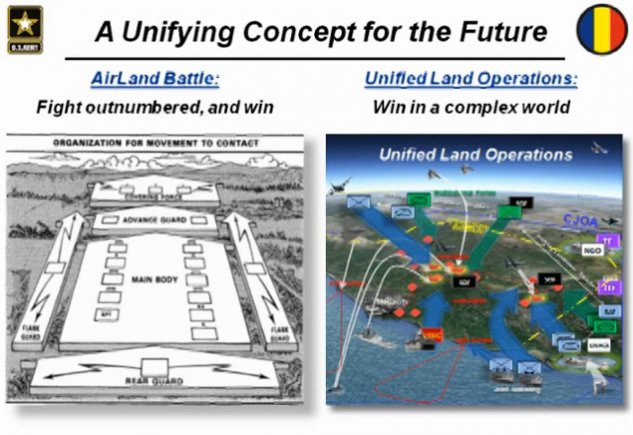

Army combat doctrine has grown more complex since the 1980s heyday of AirLand Battle.

Q: What does “convergence” mean, though, especially compared to traditional Army concepts like “synchronization”?

A: We had discussions two years ago, about what’s the difference between convergence and synchronization. And it really has taken me a long time to begin to get my head wrapped around that.

Synchronization is football. You run a play, you take 35 seconds, you huddle, you call a new play, you adjust based upon what the defense is doing or what the offense is doing. You rotate people in and out. You go sit on the sideline, you drink water, you don’t pay much attention. In the Super Bowl, there’s 14 and a half, maybe 15 minutes of contact during the entire 60-minute game.

That’s kind of the Cold War, AirLand Battle mentality of synchronization.

Then you look at hockey: a 60-minute game again, with 58 minutes of contact. You’re constantly doing offense and defense all at the same time. If you’re subbing in and out of the game, there’s no timeout, you still have to pay attention to what’s going on. And the constant coordination of players on the ice is more like we’re talking about for convergence.

SOURCE: Army Multi-Domain Operations Concept, December 2018.

Q: How well can we actually coordinate in the chaos of combat, though? We’ve been overly optimistic about being able to “lift the fog of war” in the past. What happens when, say, a young lieutenant has all this great data one minute, and then next they’re jammed and it’s all cut off?

A: Yes, that will happen.

How do you address that when it happens? We have to continue to train the way I grew up: map and compass, pace counts. We’re going to have to continue to train them like that, because it will happen.

We’re going to have to figure out how to make it happen [in exercises] at places like the National Training Center, the Joint Readiness Training Center, the Hohenfels training center in Europe, and at home station — so we ensure that soldiers can continue to operate in a degraded or denied environment.

So, what you described in terms of a lieutenant operating blind — I think that will happen. I don’t think it will happen across an entire joint force simultaneously. I’m not saying never. I do think disruption, denial will happen. But it will be in specific areas for specific amounts of time.

We have given ourselves a pass for too long saying there’s nothing we can do about that. That is one of the things we’re going to have to figure out through anti-jam capabilities, different waveforms, multiple alternative paths. On your iPhone, right, do you pick out 5G or LTE or WI-FI? No, it just figures it out automatically.

We’re not saying we’re going to solve this in the next year, two years, 10 years, 20 years. We’re going to embark upon a series of learning experiments and demonstrations, and much like we’re doing with the Capability Sets that [Maj. Gen.] Pete Gallagher and [Maj. Gen] Dave Bassett are building, we’re going to make it better every year.

We’re going to learn, and nobody is saying this is going to be cheap, easy, or quick. But if you don’t set that target out there and start working toward it, you’re definitely not going to get there.

This is going to bring together efforts across all the Cross Functional Teams. It’s going to bring the efforts across all the 31 plus 3 signature systems. It’s going to bring the cloud architecture into this, it’s going to bring data standards into this, it’s going to bring data architectures. This is going to drag people kicking and screaming in to establish that mission framework. It’s going to bring in other agencies in terms of the use of space for sensing.

It’s really all-encompassing and it’s going to force us to think through systems engineering. How does all this work together?

We talk about AI all the time. To me, AI will allow commanders and soldiers to make better decisions faster. So even if you have an AI system in middle of this and it says, “Hey, your best pairing [for this target] is a Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon,” I may say, “yeah, I only got two left. I probably want to save that, because I don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow.”

Q: We want humans in control. But what if our adversaries let the AI kill targets without waiting for a human to approve? “Go find anything with a 97.8 degree body temperature, if it doesn’t respond with our identification code, blow it up.” Can we fight that with humans in the loop?

A: There is a potential for what you described. Do I think it’s insurmountable if that happened? I don’t.

It will be a debate. Not that I’m advocating for terminators and killer robots, but I do think we need to have this discussion. Because in other parts of the world, this discussion is not going on. It will never go on.

Ultimately, the American people, through their elected representatives, decide what the policies are going to be. And ultimately the Army has always been faithful servants. The secretary published AI guidance for the department, so we’ll follow the guidance we’re given.

Do I think it’s insurmountable? No. Because I think our ethics and our concern for the value of human life are actually a strength and not a weakness.